|

First published 29th January 2019 British Medical Journal

https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2019/01/29/jane-pightling-designed-in-the-right-way-social-prescribing-could-deliver-huge-benefits-lets-not-waste-it/?fbclid=IwAR0sgccwjpqV72Bu9E8HfkGwtXwiUUBYvUaz3Wt3egjuwIZgj3xxlXPCFZU

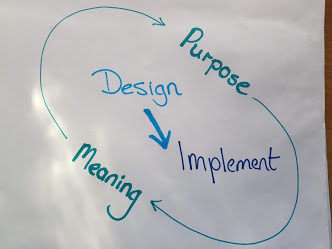

There has been much discussion about social prescribing since funding announcements were made over the summer. Yesterday it was announced that more than 1000 link workers will be recruited by 2020-21 to help with social prescribing. I understand the appeal. I recently worked with a group of GPs who despaired that what they had on offer could not help most of their patients. Many of the people they saw did not need diagnosis or treatment, but access to social opportunities, debt advice, or lifestyle support. Social prescribing can help us feel that we are doing something useful, and it also taps into the prevention agenda. How much more efficient we could be if we prevented illness. However, I have some concerns. Social prescribing is being talked about as a new panacea. I think it could make a difference, but only if we agree its intended purpose and deliberately align our approach to this. Is the aim to reduce demand in GP surgeries to help manage increasing demand? An aging workforce and difficulty recruiting and retaining staff compound capacity issues. GPs aim to provide what their patients need, and they want to make a difference. Some hail social prescribing as a return to the service they used to provide 25 years ago, before the implementation of the 10-minute appointment. Diverting demand to a community marketplace and seeking to reduce future demand in this way could be helpful. But, this aim is about moving demand in the system from one place to another, and does not challenge the system itself. Social prescribing is also described as a lever for change, which aims to redefine medical practice, help GPs embrace a holistic approach, connect with the communities they work within and deliver person-centred care. It has been reported as a radical new way of working. An approach to deliver the prevention agenda thereby reducing demand permanently and creating a sustainable health and care system for the future. These aims are transformational, they intend to change power relationships, beliefs, and attitudes that underpin our practice, and the way we design and deliver services. I believe this initiative does have the potential to deliver transformation. Social prescribing could be a way to build communities and individuals who are health literate, motivated, and resilient enough to promote their own health and wellbeing. However, social prescribing can only deliver this if we act intentionally and align the way that we design and deliver the programme with this purpose. We need to learn lessons from other similar initiatives. The story of Sure Start shows how we can unintentionally destroy social capital in a well-intentioned attempt to improve things. The evaluation showed how Sure Start adversely impacted on existing community provision for young families such as playgroups and how the Sure Start services were used more by families from higher socio-economic groups. I recently spent time with a small community arts project. They told me GPs want to refer to the project, but are unable to. Referrals can only be made to services that have been funded by social prescribing money. The arts project will close soon as their previous funding source has ceased. But there are some positive examples. The “social prescribing” that has been taking place in mental health services for over a decade has much to teach us. Initiatives such as Creative Minds which is run with South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust have achieved impressive results. The approach that they used gave resources and the power to decide how to deploy them to the people who would use the services. If we ignore this learning and continue to use traditional language, thinking, and tools to implement social prescribing then, we will not deliver transformational results, but perpetuate, and maybe even worsen, the current situation. The words “social prescribing” do not challenge the traditional medical sphere, but reinforce it. Accessing these resources requires a visit to and referral from the GP. As funding is directed to support this scheme, GPs will become gatekeepers to services that people used to access directly. Deprived of funding, the provision people used to attend independently will cease. We may unwittingly increase dependency, rather than promote independence. If we intend to deliver something radical, we must design services in a way that involves GPs in civil society and which can manifest the community’s own definition of health and wellbeing. For communities to promote healthy lives, we need to recognise their strengths, delegate power and resources, and trust and support them to build resilience. To deliver change in the system we will need to change ourselves, our attitudes, the way we work, and our relationship with citizens and communities. Designed in the right way this initiative could deliver huge benefits, let’s not waste it. The Sustainability and Transformation Planning process challenges health and social care to achieve two huge tasks. Redesign and build a new system around the needs of people and communities and do it in a financially sustainable way. To add to the complexity STPs are caught in tensions between central government and local control, long term aspirations and short term crisis and the recognition of the potential to realise huge change against the scepticism that this is just another way to cut budgets and services. It’s not only the outcomes and environment that are challenging. To succeed the system and the people in it must begin to work in a whole new way. Local leaders have been given joint responsibility to deliver. This demands a refocus from the internal hierarchies and individual organisations to spanning boundaries and building authentic relationships and networks across the landscape. Changing demographics and demands; depleted financial and staff resources; new technology; changing patient, staff and community expectations and redefining of illness, health and well-being all combine to create a complex, unpredictable and sometimes volatile environment for this work.

To work well as systems leaders, thinking beyond the usual focus of one organisation and instead holding what benefits the whole system requires relationships built on trust, shared values and the ability to appreciate contributions from all parts of the system. It also requires a huge change of perspective. We need to move from organisation based discussions focused on acute hospital ward closures to apply generative listening to the people and community who need the services and the staff who are passionate about and committed to providing it. When we take a step back and look at this challenge, it is obvious that conventional change management alone cannot deliver. It would not be efficient in terms of use of management staff and resources, or effective in terms of facilitating the innovative and inclusive approach that this task requires. Leaders need to set clear direction, boundary the space with information about standards, available resources and needs and then step back and empower and enable their staff and communities to develop, own and execute the changes. This is an anxiety provoking situation and travelling the road together is always slower than forging ahead as individual organisations or services. So, despite the pressure we must progress at a measured pace if it is to be done sustainably. It is because leaders are now fully appreciating the situation and achieving the confidence to hold the space and step back that Communities of Practice are becoming a popular way of working. Communities of Practice work first to bring people together around a shared interest or domain. This can be a professional or academic interest and can also be about personal or lived experience. Bringing different expert experiences and tacit knowledge together and enabling people to develop shared stories, collective sense making and shared values develops a group identity and relationships where deep learning and new knowledge and practice can be developed. Communities can bring people together across traditional boundaries, encourage groups to identify their most burning questions and facilitate them to co-create new knowledge and practice in response to the most complex challenges. Staff involved in this way of working have reported a reconnection with motivations and values that they felt had been lost in their work. Patients, service users and carers spoke about being heard and valued as their experiences were validated and aspirations recognised. Perhaps most importantly Communities are generating innovative, sustainable solutions to sticky problems and creating real value for themselves, their organisations and communities. Proof perhaps that “None of us is as smart as all of us”. |

AuthorJane Pightling has experience across the public, private and charitable sector. Through her work in the NHS Leadership Academy and her consultancy Evolutionary Connections she developed complex systems leadership capacity, providing training, coaching programmes and establishing networks and communities of practice to sustain learning. She maintains her social work registration and her commitment to person centred and community focused approaches. Jane has a deep interest in the potential offered by new ways of working, designing and building organisations and communities that can best deliver this kind of service. She works with organisations and leaders to develop approaches that design in autonomy, wholeness and purpose. Archives

October 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed