|

First published September 2021 How we merged the CIH Professional Standards with our own values : Housing Digital

Although the CIH Professional Standards initially posed a conundrum for LiveWest, who had launched their own standards just months before, Leadership Development Lead Jane Pightling explains how the two sets of values were more compatible than it first seemedWhen the CIH launched its Professional Standards in March this year it felt like a landmark moment, a huge leap forward for the professionalisation agenda. At LiveWest, we are aware of the huge challenges the sector is facing. Decarbonisation, an increased demand for housing, supply chain and recruitment challenges, the need to clear the backlog of works created by COVID-19, and the uncomfortable glare of media attention on the sector. Next to these complex challenges, Professional Standards can seem like a sideshow. At LiveWest, we have not been subject to media attention, but we feel the impact and we are wrestling with everything else. Our colleagues have been working hard, but there are still things we want to do better. We are currently engaged in a culture programme using symbols, systems, and behaviours as levers. Our values – 10 behaviours and 25 culture descriptors – were developed with colleagues and customers, and we launched Our Behaviours a couple months before the CIH launched the Professional Standards. The launch of the Professional Standards presented us with a bit of a dilemma. We believe the CIH professional standards are significant: they can help to enhance the professional reputation and capabilities of people who work in social housing, improve the quality of service to our customers, and promote the standing of the whole sector. We want to collaborate, unify our voice and work with others across the sector. At the same time, we are proud of our LiveWest values, culture, and behaviours; and we want to take them with us into our future. We also want all colleagues across LiveWest to be able to use one framework to know what is expected of them and not have to use several frameworks or duplicate work. Our challenge was to integrate all these ambitions into an aligned approach that could deliver all of these outcomes. We mapped the CIH Professional Standards against Our Behaviours and found that, although we used different language and grouped the elements differently, all Our Behaviours link to and cover all of the CIH Professional Standards. For those that prefer a simple format, we created a table cataloguing the links. For those that prefer a big picture view, we used KUMU to create an interactive map. We summarised the work into a document called QuickStart Guide, so all colleagues can easily access the information and find links to the detail of Our Behaviours and the CIH Professional Standards as needed. “We mapped the CIH Professional Standards against Our Behaviours and found that all Our Behaviours link to and cover all of the CIH Professional Standards” Colleagues started to use Our Behaviours in their day-to-day work, interactions, team meetings, performance, and development reviews and communications. They are helping us all to focus. Not just on what we are doing, but how we are doing it and what we stand for. They are the key to professionalisation and delivering great services to our customers. Recent feedback from colleagues also revealed this work as a useful resource for anyone completing CIH qualifications and considering how Professional Standards are being used in their day-to-day work and across the business. The Professional Standards can help with many of the challenges we face in social housing. Not least, they can help us step up and claim our professional identity as housing colleagues. To nail our colours to the mast in terms of our commitment to the highest standards of behaviours and ethics. I think it’s always been the case that a group of skilled, talented, and passionate individuals operating in the wrong environment or culture can, without malice or intention, fail to do good or even do harm. Our Behaviours and CIH standards provide the golden threads that will be woven into the fabric of our systems and processes as we continue our culture change work at LiveWest. Now we have these standards, our next job is to create the culture that promotes and enables all of us to live up to them. I have noticed over the past couple of days, an increasing number of posts from distraught or angry people who are unable to buy the goods they need in the shops. The exhausted hospital worker and the angry carer of an elderly or disabled person write posts that can move us quickly to blame and condemnation. I am not underestimating the impact of this experience, indeed what I am noticing is how this impact builds.

It may be that there are a group of people who have food stocks in their garages and sheds, spare rooms bursting with toilet paper and hand gel and boxes of paracetamol and medicines under the bed. However, I think this group is probably small. Moreover, I think this group may be especially anxious and fearful and that this will be a huge burden to live with over the next few months that no amount of extra toilet roll will assuage. A much bigger group is the rest of us. From what I can understand about supermarket logistics, it seems that the supply system is very intelligent and usually delivers what we need, just in time, so minimising costs of storage and waste and maximising profit. It seems it does not take much to upset this balance. It may be very logical to plan in case we are ill. Not a selfish act but a generous one. Sensible measures so we don’t put pressure on other family members or a community who would need to shop for us if are incapacitated. A packet of pasta, tin of beans and a pack of toilet rolls would hardly be considered “panic buying” by most people and yet, if it is not what we would usually buy, when you add it all up, it will impact on the supply chain. Add to this the idea that our purchasing behaviour is not rational. If it was just a logical decision based on need, the marketing and advertising industry would simply not exist. So just telling us not to “panic buy” is unlikely to have much impact. Most of us would not identify buying a little extra as panic buying. Previous studies, such as that presented in Butterfly Economics, demonstrated how the interaction of many factors can cause behaviour to suddenly switch and that our behaviour is far from predictable. If we view changes in purchasing patterns through this lens then what we have termed “panic buying” is not irrational either, it is informed by a range of information and experiences. It is true that some supermarket shelves are empty, that toilet rolls are often not readily available, and this is an experience shared by our family and community and will naturally impact on our thinking, emotions and behaviour. The issue seems to be that we are thinking about this as a simple problem with a linear cause and effect. People are buying too much which means others are being left without. We then overlay this with a moral judgement. With no real understanding of what we mean, we label the people who are “panic buying” as selfish and bad. The result of this thinking plays into the complexity of the situation that we are failing to identify. My sister worries that if she does the shopping for my elderly mother and her elderly neighbour too, that the people at the supermarket will condemn her as a selfish panic buyer. Meanwhile we issue advice that elderly people should not leave their homes and that we all should limit the number of visits to the shops, perhaps going less often and buying more than we would usually to last over a longer period. We create even more anxiety, fear of being judged by others, fear of disobeying the rules of going to the shop too often and buying too much, and fear or being without the goods we need. We cannot meet all these contradictory demands and we get even more stressed and anxious. By failing to identify the complexity of the issue and work with it in this way, we are unable to address it. Indeed, by adding a moral judgement into the mix we are likely to create more problems. It is not Coronavirus that is creating this issue but a virus of fear and uncertainty. By failing to recognise the complexity and applying simple moral judgements, we are building on the problem, feeding the fear and creating new problems. If we can see this, then we can choose to stop. First published linked in March 2020  Image Synthetic Biology: Externalising the Internal” by Ahreum Jung is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 It was a pleasure to read the Quality & Safety article by Andrew Smaggus published last summer by the BMJ. At the same time I was working with colleagues from the Evolutionary Transformations Group (ET Group), on the impact on our wellbeing of the way we think about and relate to challenges in a complex world. Reflecting on my experiences as a clinician, manager and improvement lead, Smaggus’ thinking made perfect sense. The concept of creating a new Safety-II paradigm based on concepts from complexity science is exciting and potentially liberating for both caregivers and receivers. Safety-I defines success as the absence of failure; the fewest number of things going wrong. There is a best practice or good practice ideal and clinicians are expected to act in line with this. Snowden’s Cynefin model advocates best practice when faced with an obvious challenge, a challenge where there is a clear cause and effect relationship apparent to all involved. There are such challenges in health care and Safety-I thinking has been extremely useful in establishing safe systems to support the correct use of equipment or the best way to conduct a routine procedure in usual circumstances. In a recent visit to hospital, my temperature and blood pressure were monitored and my blood was taken. The HCA followed best practice procedures to obtain the result she needed, and I suffered no harm. When faced with complicated problems the clinician applies their expertise to identify the relationship between cause and effect. In my recent experience, the doctor assessed the problem I was presenting with, analysed the information available and decided on the best response using good practice. This is a situation in health care where we often feel most at home. As clinicians we are confident in our expert knowledge and competent in the mastery of our specialist skills. As a patient we are given a right answer and a clear offer of treatment or cure. Given the efficiency and security we experience when operating in the face of obvious and even complicated problems, it is perhaps no surprise that we often misidentify complex issues as belonging in this space of ordered challenges. As Smaggus discusses, there is a growing body of evidence that tells us what we already experience to be true, that these approaches are not successful in dynamic unpredictable or VUCA environments (volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity). In these circumstances the ability to sense and respond, to provide a creative, agile and adaptable approach is most likely deliver success. Our ET Group workshops found that supporting people to occupy a resourceful state and develop confidence to access their Complex Human Adaptive Intelligence was successful in enabling them to be well and to operate successfully in a VUCA environment. In complex and unpredictable circumstances, strict adherence to best practice procedure or good practice guidelines is not advantageous. Smaggus identifies that the Safety-II approach which focuses on what goes well has much to teach us here. He cautions that in failing to recognise what goes right we also fail to see the things that may be exhausting and frustrating to people in their everyday work. In my experience, every health and social care worker can tell you about a standard policy or procedure that makes doing an everyday task much harder to do well. Our focus on fails can also blind the system to the extra work being done by people to maintain good outcomes. In this situation, long hours, missed breaks and working on days off and holidays become the norm. If Safety-II approaches were being applied, what would we do differently? Would caregivers and receivers be eating lunch together? Would we invest time celebrating holiday taken rather than investigating days off sick? In our ET Group workshops, we also identified the detrimental effects of attempting to work with complex challenges when misidentifying them as ordered problems. When we do this our best or good practice solutions fail or result in temporary, unsustainable quick fixes. We merely store up more challenges to be sorted in the future or beat ourselves up with self-accusations that we are incompetent, careless or didn’t work hard enough to generate the correct solution. The way our systems and organisations respond frequently reinforce this, investigating deviation from standardised process and identifying individuals to blame and punish. The impact on our wellbeing and connection with our work is devastating. Smaggus identifies the effect of Safety-I approaches, which elevate the importance of the regulatory systems and those who design and operate them above the knowledge and experience of clinicians, and the resulting impact on engagement with work. I would suggest that there is further impact. That this approach and the paradigm it is based upon is in part responsible for sucking the humanity out of health care. The emphasis on technological solutions, standardisation and control excludes things that cannot be readily codified. We know that safe, high-quality healthcare is most likely to happen in the context of a trusting and caring relationship. Activated and engaged patients are less likely to come to harm, and valued and present staff are more able to work confidently within an unpredictable environment. These staff will be able to respond appropriately to meet the individual needs and preferences of their patients. The blanket misapplication of Safety-I and standardised approaches do not align with our aspirations to provide high quality, person-centred care. As we continue to struggle to cope with demands on an individual, organisational and system basis Smaggus makes a vital point. It is only by adopting Safety-II thinking and appreciating how to better support the many successes of normal everyday work that we can provide the resilience and flex to enable us to continue. He identifies a very uncomfortable truth; the modern scientific paradigm is no longer enough. It has a role to play in supporting safe practice in everyday straightforward tasks but cannot address the complexity of our current situation. Continued failure to recognise this will perpetuate stress and burnout for staff and continue to create unresponsive, low quality and even unsafe experiences for patients. https://q.health.org.uk/blog-post/a-closer-look-staff-wellbeing-and-safety-in-the-complex-world-of-healthcare/ First published by Health Foundation Q community 7th February 2020

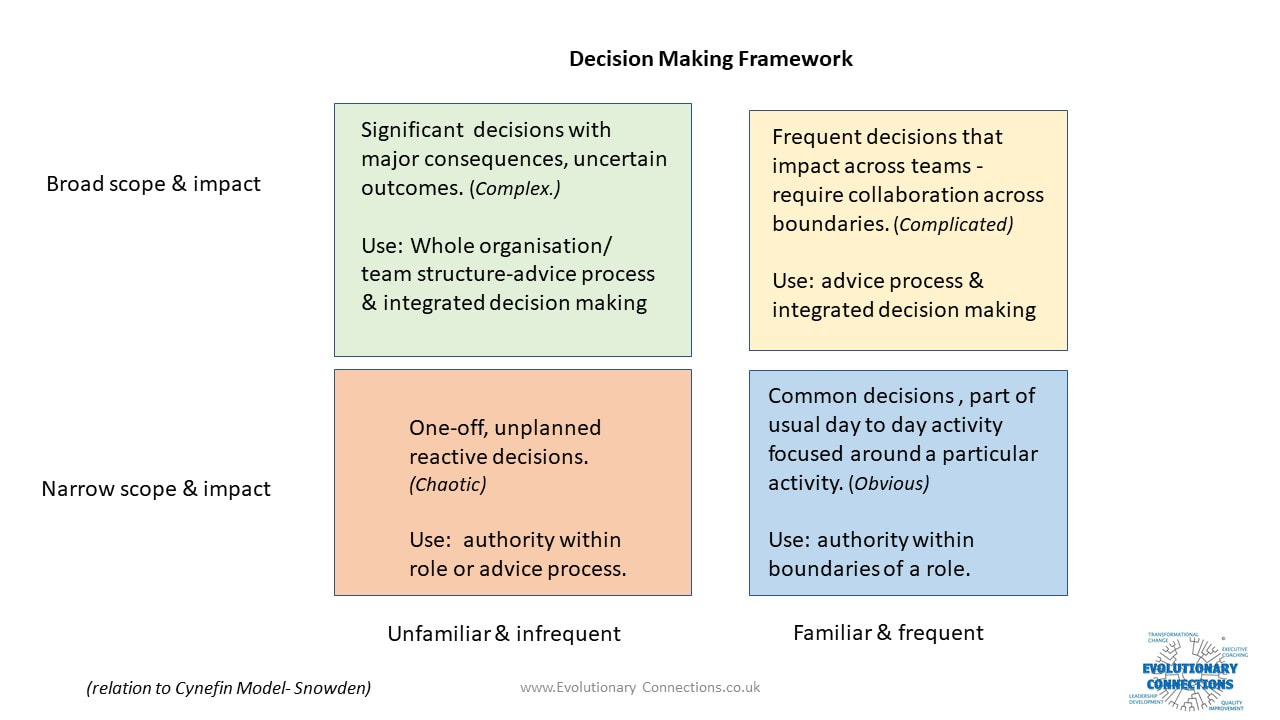

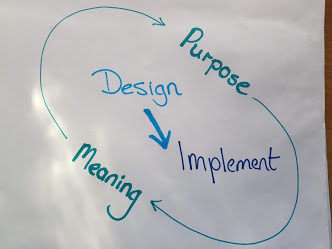

Working with organisations to create new ways of working which enhance autonomy, mastery and meaning; one of the areas that causes most anxiety is decision making. Although the current decision-making structures and processes are often not working, there is a comfort in the system we know, however flawed. When we think about changing the system people worry that they won’t make good decisions while others worry that handing over decision making will lead to chaos and disaster. Once we recognise and own the emotions that are connected to this task, we can put them to work. A decision audit is often a good place to start, coupled with an amnesty that recognises what we set out as the process or structure and what actually happens are likely to be two very different things.

Although we know it isn’t working; when we see the number of sign offs and handoffs, recognise the pseudo- delegations that are really “you decide but only if I agree” and track the decisions that are being taken by the wrong people in the wrong place at the wrong time; it can be a shock. It is also common to find organisations that are not clear about how decisions get made. Decisions are made by whoever happens to be there, at the time they need to be made with whatever information happens to be to hand. Sometimes unforeseen circumstances require this type of decision making but these situations should be few and far between. When we appreciate what is really happening in our current system, we can easily locate the reasons behind the tensions and conflicts, the confusions that lead to mistakes and inefficiencies and the frustrations that lead to disengagement and poor-quality work. Following a decision audit, we can identify what sort of decisions we require and locate decisions within roles, teams and processes. Designing a good enough to try and safe enough to fail system enables the organisation to make a smooth transition and design in processes that require the design to be reviewed and improved as the new way of working matures. I designed this Decisions Making Framework to help organisations recognise the type of decisions they are making and locate them in the most appropriate place in their design. If you would like more information or support to enable your organisation to make this transition and achieve better decision making, please don’t hesitate to contact me. It’s hard work setting up a business. Research shows moving from start-up to scale up presents new and equally demanding challenges. High growth organisations face challenges in recruiting the right talent to meet their growing needs, developing the leadership to continue to inspire and steer the organisation, the perennial access to finance issue and the need to create the right structure and culture capable of delivering the vision.

As more businesses become clearer about their vision and commitment to values, so more start-ups seem to reach a situation where a choice needs to be made. Many make the decision to stay small so that they do not compromise their values. Others sell out to larger organisations, checking out before the original vision is compromised. But there is another way. I have recently been working with a small company committed to sustaining great relationships and flexibility for its staff and delivering high-quality services for its customers. Supporting people with disabilities at home, and in hospitals and schools; this company also wanted to make its services accessible to everyone it could it make a difference to. Growth was in line with its values and essential to delivery of its purpose. This company could not stay small and align with its values, it could not limit its growth and fulfil its purpose. On the other hand, the co-founders were adamant that they did not want to develop into a hierarchy with layers of management, bureaucracy and tomes of policies and procedures. This was not what they were about. They were at a crossroads and took the brave decision to find another way that would promote sustainable growth, align with their values and help them live the meaning of their organisation. Taking a new approach to developing an operating system and organisational design that intentionally creates the culture you want and promotes the values you founded your business on, is a realistic and prudent option. There are now thousands of organisations adopting self-managing techniques and creating their own non-hierarchical organisational structures. Asking new questions, they find answers to attracting, growing and retaining the right people, being agile and remaining relevant to their customers, staying true to the original purpose and therein delivering the real value of the business. They found that all can be more successfully delivered by adopting these new ways of working and growing their organisation. Entrepreneurs are by nature innovative problem solvers, adept at creating new opportunities. It’s vital to embrace innovation and seek new solutions in all aspects of your enterprise. There is a huge opportunity for growing businesses to exploit by adopting these new operating systems and agile structures. Time to ask the new questions, how can I stay true to my values and grow a successful business? Lots of growing businesses are already finding out. Reflecting on my experiences of bringing new ways of working to organisations working in health and care in the UK led me back to Laloux and the section in the illustrated version of his book which I have used often. It discusses the many ways to start. Whilst I accept the experiences of colleagues working into other sectors and in other countries, in the UK statutory health and care sector I think that first method described, experiment in a team, is being misused. This is particularly true in the NHS. There are examples where new teams have been established as pilots and have produced great results, delivering real benefits for the staff, care receivers and their families. However, these projects continue to exist in isolation or once the pilot period is over or the extra funding runs out, the project is closed. This is not unique to the area of self-managed teams, there are other innovative and progressive projects that have produced great results and been closed at the end of the project term. Often at best, a diluted version of their new learning and practice survives and is transferred into a traditional system which sterilises and assimilates it into its mainstream thinking.

Brian Robertson writes about how “corporate antibodies come out and reject the bolted-on technique, a foreign entity that doesn’t quite fit the predominant mental model of how an organisation should be structured and run.” I think this perfectly describes what is happening to many of these projects and pilots in the NHS. They are hosted for prestige and welcomed for the extra resource that comes with them, but there is no commitment to change in the wider host organisation. Unless we commit and work to achieve a real paradigm shift in the host organisation and wider system, the pilots and projects will continue to fail to realise their full potential. When we do this, we waste time, money and energy and most importantly erode the hope and motivation of the people involved in the pilot work. Whilst we cannot change a huge organisation instantly we can build intentional architecture to support transformative change.

First published 29th January 2019 British Medical Journal

https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2019/01/29/jane-pightling-designed-in-the-right-way-social-prescribing-could-deliver-huge-benefits-lets-not-waste-it/?fbclid=IwAR0sgccwjpqV72Bu9E8HfkGwtXwiUUBYvUaz3Wt3egjuwIZgj3xxlXPCFZU

There has been much discussion about social prescribing since funding announcements were made over the summer. Yesterday it was announced that more than 1000 link workers will be recruited by 2020-21 to help with social prescribing. I understand the appeal. I recently worked with a group of GPs who despaired that what they had on offer could not help most of their patients. Many of the people they saw did not need diagnosis or treatment, but access to social opportunities, debt advice, or lifestyle support. Social prescribing can help us feel that we are doing something useful, and it also taps into the prevention agenda. How much more efficient we could be if we prevented illness. However, I have some concerns. Social prescribing is being talked about as a new panacea. I think it could make a difference, but only if we agree its intended purpose and deliberately align our approach to this. Is the aim to reduce demand in GP surgeries to help manage increasing demand? An aging workforce and difficulty recruiting and retaining staff compound capacity issues. GPs aim to provide what their patients need, and they want to make a difference. Some hail social prescribing as a return to the service they used to provide 25 years ago, before the implementation of the 10-minute appointment. Diverting demand to a community marketplace and seeking to reduce future demand in this way could be helpful. But, this aim is about moving demand in the system from one place to another, and does not challenge the system itself. Social prescribing is also described as a lever for change, which aims to redefine medical practice, help GPs embrace a holistic approach, connect with the communities they work within and deliver person-centred care. It has been reported as a radical new way of working. An approach to deliver the prevention agenda thereby reducing demand permanently and creating a sustainable health and care system for the future. These aims are transformational, they intend to change power relationships, beliefs, and attitudes that underpin our practice, and the way we design and deliver services. I believe this initiative does have the potential to deliver transformation. Social prescribing could be a way to build communities and individuals who are health literate, motivated, and resilient enough to promote their own health and wellbeing. However, social prescribing can only deliver this if we act intentionally and align the way that we design and deliver the programme with this purpose. We need to learn lessons from other similar initiatives. The story of Sure Start shows how we can unintentionally destroy social capital in a well-intentioned attempt to improve things. The evaluation showed how Sure Start adversely impacted on existing community provision for young families such as playgroups and how the Sure Start services were used more by families from higher socio-economic groups. I recently spent time with a small community arts project. They told me GPs want to refer to the project, but are unable to. Referrals can only be made to services that have been funded by social prescribing money. The arts project will close soon as their previous funding source has ceased. But there are some positive examples. The “social prescribing” that has been taking place in mental health services for over a decade has much to teach us. Initiatives such as Creative Minds which is run with South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust have achieved impressive results. The approach that they used gave resources and the power to decide how to deploy them to the people who would use the services. If we ignore this learning and continue to use traditional language, thinking, and tools to implement social prescribing then, we will not deliver transformational results, but perpetuate, and maybe even worsen, the current situation. The words “social prescribing” do not challenge the traditional medical sphere, but reinforce it. Accessing these resources requires a visit to and referral from the GP. As funding is directed to support this scheme, GPs will become gatekeepers to services that people used to access directly. Deprived of funding, the provision people used to attend independently will cease. We may unwittingly increase dependency, rather than promote independence. If we intend to deliver something radical, we must design services in a way that involves GPs in civil society and which can manifest the community’s own definition of health and wellbeing. For communities to promote healthy lives, we need to recognise their strengths, delegate power and resources, and trust and support them to build resilience. To deliver change in the system we will need to change ourselves, our attitudes, the way we work, and our relationship with citizens and communities. Designed in the right way this initiative could deliver huge benefits, let’s not waste it. A Tactical Meetings is a meeting which uses a specific process to structure discussions and decisions. The process is part of the holocracy model and is often adopted by self-managing teams. Holocracy, and some of the processes it uses, can be very appealing to teams and organisations which prefer to focus on what needs to be done in order to become self-managing. Good processes can be hugely beneficial and in health and care and better ways of getting things done are very attractive. They tap into the concern we have about efficiency and spending as much of our time and resource as possible with the people we are caring for. Minimising the time spent and maximising the efficacy of meetings is a good thing. However, if teams and organisations are not also paying attention and dedicating time and effort to the issue of wholeness; adopting these methods and misapplying selected elements of holocracy can make current challenges much worse. As the breakthroughs of wholeness and evolutionary purpose are often more challenging for traditional health and care organisation and their leaders, there is a tendency to focus on the self-managing team aspect and concentrate on processes that enable this. Below are two case examples from my work which help illustrate this.

Tactical meetings were adopted by a new subsidiary business set up to be self-managing. It involved a team spread over a large geography. The new business intended to make good use of technology and be very efficient with time. Team members would not need to meet unless they were delivering a service together. All team interactions were online and tactical team meetings took place as a video-conference. Some staff worked part time for the new subsidiary business and part time for the parent company. Team members working in the established parent company met regularly in their shared office and naturally transacted business for the subsidiary company in this existing office space too. As holocracy had not been adopted as a whole system, there were gaps in communication information was not accessible to staff located outside the physical office. In the subsidiary company Tactical Meetings were held weekly and lasted between 30 minutes and an hour. Members not present in the parent company office found these meetings confusing and unhelpful. They often felt ill-informed, excluded and frustrated that there were not enough opportunities to discuss their work and develop relationships with colleagues in the Tactical Meetings. There was no other opportunity outside them. Staff working in the parent company office viewed the dissatisfaction expressed as due to the new team members having difficulty adjusting to the Tactical Meeting process and advised them to read the holocracy literature. Relationships had not developed that enabled these difficult issues to be discussed in more depth. The subsidiary business struggled to make progress and the team saw a 40% staff turnover rate in its first year. In a large organisation an established team had problematic weekly team meetings that lasted at least 2 hours. Staff were frustrated that these meetings often failed to make progress and some team members admitted to avoiding them if possible. The team agreed to try a Tactical Meeting approach. They found it tough to comply with the rigid format and at first, keeping and updating records and formally preparing proposals outside of the meeting felt like an extra task the team did not have time for. The team persevered and within a month the tactical meeting process enabled weekly business to be progressed in 30 to 40 minutes. The team paid close attention to relationships and wholeness in developing their work together as a self-managing team. The Leadership did not demand the time released by the Tactical Meeting process to be turned over to more “doing” but allowed the team to make its own decisions about how to use the time. The team used it to implement new practices which strengthened their relationships and ability to be together. In the newly released “Team Time” staff brought their lunch to share to the first 20 minutes of the meeting and used it to catch up with each other as colleagues and friends. They then scheduled the remaining time to concentrate on things that they viewed as important. This included discussions on new best practice and legislation, enabling them to develop professionally as individuals and as a team. They also held discussions about how they were experiencing organisational policies and the impact these were having on their practice. These conversations explored how their work was aligning with their team and personal values and purpose and informed actions they took on this. Deep conversation and learning enabled significant enhancements of practice to the benefit of the organisation. This was possible because of the attention paid to the needs of team members and developing and maintaining trusting relationships in the team. New ways of working deliver real benefits when all aspects are pursued with intention. It is possible to implement self-managing processes in isolation from wholeness and evolutionary purpose, but these will not deliver and may even cause harm. Whilst it can seem a familiar and attractive option, the focus on processes alone help perpetuate the thinking, attitudes and behaviours which created the challenges we currently face. Only by focusing on practice and adopting practices that enable wholeness and enhance our ability to sense and pursue purpose can self-managing systems deliver the benefits they promise to health and care. Transitioning to a new way of operating is big. It is not only about the processes but perhaps more importantly about the culture created and developing people to work well within it. Like the world of private business, leading an organisation into this transition will require courage, creativity and authenticity. A body of work has been generated on organisations setting up to be self-organising. Laloux is currently focusing on organisations making the transition. In my work in health and care I have tried to build on Laloux’s insights. These are the foundation stones I have found to be essential in setting the scene for successful and sustainable progress. 1. Declare your intention.David Marquet talks about developing distributed leadership by announcing intent. It is important to lay good foundations to build upon and to prepare an organisation for the change. Communicating in a way that models the vision you are hoping to achieve is vital. All staff, regulators and stakeholders, leadership and the communities it serves must be aware of what is being planned. They need to hear about it and be inspired to talk about it and explore it. There will be many levels of awareness and understanding in an organisation and wider community. Many staff will view this as another management fad. People are busy and have day to day tasks to focus on and may not see this as a matter they need to pay attention to. Socialising the approach and the intent to move in this direction is key and worth taking time and effort over. It is vital that organisational leaders are leading this process, staff and the community need to know that leaders are signed up to this. Being able to articulate the vision, explain the challenges it answers and the opportunities it offers is a leadership task. Using the narrative to connect to the values and purpose of the organisations past and project and reinvent these for the future will inspire people to action. 2. Align values and approaches across the organisation and communityMaking firm connections between the ethos of care and the values that underpin this and the way the organisation operates helps people make sense of the direction being taken. In health and care increasing demands are being met successfully with work which is

Organisations moving in this direction must successfully align person centred approaches to care, customer focused approaches to corporate services, self-managing approaches to operating systems and underpin these with values and behaviours that demonstrate a commitment to wholeness and delivery of purpose. 3. A clear line of sight for values and purpose. Once people begin to understand what the vision is about two needs will surface. The first is around aligning individual values and purpose with teams and with the organisation in its new form. Many organisations have purpose and value statements that provide decoration on the walls. They are not evident in the behaviour, processes and decisions of the organisation. An organisation needs to review its purpose and values. It needs to appreciate and acknowledge the values that have brought it to this point and to ask if these are the values that can deliver it into the future it has envisioned. An approach that creates the space for people to explore this whilst at the same time giving a clear indication of the direction and vision is needed. This can be a challenge for organisations used to operating by consensus as this is not about negotiating a compromise. 4. Expect the usual reaction to proposed change. The second need, or to be more accurate this happens concurrently with the first, is people ask what does this mean for me? Do I have job, what job, how much will I earn, where, who with, doing what, how will it work? Or, will I get a service, who will work with me, where will they work, will it be as good as now, will I have to pay, and what about…? The list of questions and the detail that people will request can be surprising to leaders who more usually concern themselves with strategic matters. If someone has been able to align their personal values and purpose with the new direction set, they are more likely to want to work through these details and co-create a solution. The direction, way of working and cultural elements of the vision may seem new but the way people react to proposed change is not. Being very clear about the direction and confident about the ability of the organisation to achieve the change is important. A huge advantage of working in health and care is a workforce that is adept and eager to solve problems themselves, but this will not happen immediately. People need to time to sense make and decide what they will contribute. There will be a segment of staff and members of the community who are supportive and see the potential, but the rest will be unsure or already have decided this is a bad idea. Whether intentional or not, within the power hierarchies that exist, mangers will influence their staff and staff influence the people they care for and support. Leaders need to be working proactively to provide meaningful opportunities to explore and to direct the change process. At this stage the Leaders will need to outline and hold the space firmly for staff to take some first steps. They will need to issue invitations to people to step up and create the next stage of the journey of the organisation’s evolution. Resources are scarce, and it is possible to send a huge amount of time and energy with people who will not be influenced to support the change. Leaders need to focus attention and follow the curiosity and energy that emerges. This can feel uncomfortable for organisations that are used to a more traditional consensus approach. 5. Activate the whole leadership team. Counterintuitively perhaps, evolving into a self-organising system requires great leadership. Leaders need to understand and be confident about their role in this new type of organisation and clear about how they can support the current organisation to evolve. Their first task is to create and tell the story about why organisation is doing this and what it will be like in the future. Leaders need to be coached and supported to hold the space and issue invitations for staff to step in and take up vital roles and pieces of work. They need to plan and to rehearse their response for when things go wrong. It is important that they are there to hold a steady course and remind each other of “how we do things now around here”. Teams that will be first to try out this way of working need to know that Leaders really mean it and that they will be supported, when things go wrong. 6. Create new ways of communicating. This means moving away from hierarchical flows of information to networked conversations where staff can see work in other parts of the organisation and contact those who can help them or make offers to those they can assist. Leaders and staff need to develop confidence in storytelling and develop more transparent communication. This is not about marketing this is about authentic exchanges between colleagues. Sharing honestly their intentions and anxieties; what they have tried, what worked and what didn’t work. 7. Create new ways of learning. Developing opportunities to self-manage and self-direct learning individually and as part of teams is essential. This may mean a move away from a set menu of in-house courses to facilitating staff to set up their own research and learning programmes. Opening conversation and sharing experiences with other organisations both inside and outside the health and care system offers huge advantages. Supporting staff to develop these skills and confidence to facilitate communities of learning and establish learning networks help to create an organisation that can keep learning and improving, a vital skill to sustain self-organising teams. 8. Practice as an organisation. Being alive to opportunities to introduce key practices across the organisation. These can be very small and support key aspects of this way of working. For example, tactical meeting processes or parts of the process such as checking in, adopting circles as a way of exploring and deciding, and integrated decision making can be useful across the organisation even before it adopts the other ways of working. Adopting these at senior levels and in forums where vitally important work is conducted sends a strong message and enables leaders to share their experiences as peer learners with other staff adopting the new ways of working. 9. Wholeness This is a part of this work that many organisations struggle with. In health and care we are confident with the rational and scientific and have recently began to work more competently with the emotional and spiritual aspects of supporting and caring for people. We do not currently feel so comfortable recognising the emotional and spiritual with our staff and in our own work. Organisations in health and care can often open this door by talking about Wellbeing. This is an arena that allows us to recognise the emotional and spiritual health of staff as contributing to our ability to provide compassionate care. Widening out this agenda to include issues that we label as equality and diversity helps us to recognise other facets of a whole person. Lifestyle, culture, sexuality, caring responsibilities, disabilities and talents are all part of a person. Previously in recognising only the “professional slice” of our colleagues that we allowed at work, we failed to recognise their talent. Getting to know our colleagues better, seeing beyond their job title and banding and recognising aptitudes and talents allows us to make best use of potential and provide meaningful fulfilling work. Without this key aspect in place and staff feeling valued and respected as people, it is difficult for staff to find the motivation and confidence to step into the arena of self -organising and there is a risk that this becomes just another type of restructure. 10. Follow the invitation and the curiosity. The move to self-managing teams is often the focus of attention but this is only enabled at scale by building on a foundation of local success. Supporting teams who are energetic and curious to test and learn about how they can use these approaches will build these successes. There may be a temptation to resort back to usual programme management methodologies and impose a roll-out schedule. There is an increasing body of research that suggest that this is not effective, and this approach does not align with the values of the work being undertaken. Teams can be supported to build on their strengths in practices and processes that already speak to this way of working. Similarly, they can identify new practices that can help them with a current challenge. There may be a set of core processes and behaviours the organisation would aim all teams will adopt. Supporting teams to start where it is most relevant and important for them is more likely to lead to sustainable success. Enabling them to report progress against minimum specifications and purpose supports the change being pursued. 11. Look for minimum specifications and maximum trust. This is an opportunity to do some spring cleaning. We are great at establishing new rules and meetings to address our latest concern and not so good at getting rid of them when they no longer serve our purposes. Asking what staff and services need to do and what must they not do is a simple way to begin to outline a minimum specification and to jettison processes and procedures that support the old way of thinking and working. Reviewing the complicated data collected and co-creating KPIs that reach into the heart of what is important to everyone can provide meaningful and robust assurance. 12. Celebrate Collect the stories and tell them inside and outside the organisations. This sounds very simple but in health and care there are anxieties about sharing our pioneering work and being criticised. A sensational press headline or hostile parliamentary question can squash innovation and lead to accusations of irresponsible practice and imprudent use of scarce public resources. There will be people who find their positions and practices threatened by these new ways of working that are keen to find evidence of failure. Its vital to set the tone. Talk honestly about our experiences, the challenges being faced and the anxieties that are surfacing. Sharing the stories about the practices that are emerging and the learning and knowledge with the wider organisation is an essential task. Most importantly is enabling the staff and the people they support to talk about being able to do what is important and how they can make a difference. Describing how they have taken tough decisions together and how they are held accountable for them. 13. Support develop and coach. The ethos that underpins this approach is about learning and development on a personal, professional and organisational level. There are already schools organised and teaching using self-organising systems, but at present most of the people currently working in or being recruited into health and care will not be skilled or confident in this way of working. Building safe environments where feedback is generative, learning is generous, and coaching is the way things are done around here is essential to helping staff and citizens thrive in this new environment. 14. Be clear about assurance. Laloux cautions “a common mistake is to get rid of existing control mechanisms without putting in place what’s needed for systems to self-correct.” This is an arena that causes much stress in the health and care system. I have experienced several Boards and leadership teams who are rich in all kinds of data processed through a range of meetings but when asked still cannot answer confidently “how do you know”? There are some key pieces of data and, some information that organisations are required to collect and report for political reasons. These measures do not necessarily add anything to our ability to assure or improve. Being very clear about purpose and values and using data and reflective techniques to understand delivery of purpose is key. Rethinking the information provided and distributing it to teams in a form that enables them to understand where they are at is a new activity for most health and care organisations. Adopting an approach of “behind every stat is a story” is also helpful in encouraging data to be linked and conversations to be held that enable us to really understand what the position is and why. 15. Continuous improvement. This is properly and closely linked to assurance. In health and care there is a focus on continuously improving safety and quality and a yearly round of cost improvements imposed on every budget. Most staff I have worked with are genuinely committed to doing better for the people they support and care for. They strive to improve in difficult circumstances. Improvement is no longer about doing the same things more efficiently but about challenging ourselves to understand the value in what we do. Moving is this direction requires us to rethink our approach to improvement and focus it around achieving our purpose and creating value for the people and communities we serve. I responded to Anya De Longh this morning. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2018/10/03/prescribing-personalised-social-pharmacological/

I describe myself as having an allergic reaction to the term social prescribing and this I think my answer below helps to explain why. It’s good that we are starting to recognise health as social and develop our practice accordingly. I worked with a practice recently where GPs were frustrated that what they could provide was not what their patients really needed. It was important to them and to most health care staff to know they can make a difference. Social prescribing enables them to do more of that. I had a conversation yesterday with someone who works for a CIC. They have a 30-year history of working with disengaged and hard to reach groups on community projects which make a difference to the individuals and help build the communities they live in. However, the CIC is under threat as the funding streams from local authorities, youth offending schemes and regeneration have disappeared. He had a conversation with a local GP, aware of the impact of the work the CIC does, who wanted to have this option on his prescribing list. However, a further conversation with the practice manager revealed this was not an option, they could only prescribe to funded projects and social prescribing funds have been cascaded down the health route. By trying to deliver a non-traditional approach in a traditional way we are at risk of further limiting the choice of the people we seek to support. We are viewing the issue through our own “health lens” and allocating resources according to our values and agenda. Activists are receiving the message that if they want to do something in their communities they must fund it themselves or rely totally on volunteers. If we are serious about empowering individuals to take responsibility for their own health and supporting communities to provide opportunities for this to happen then we need to give them the power AND the resources to do this. The issue with social prescribing, which is reflected in the language we use is the power and control. Social prescribing is a good start. I hope that as we change the language of this developing practice we can change the attitudes and the behaviours that underpin it too. We just need to do this quickly or the further community assets that are being starved of resources will wither and die. |

AuthorJane Pightling has experience across the public, private and charitable sector. Through her work in the NHS Leadership Academy and her consultancy Evolutionary Connections she developed complex systems leadership capacity, providing training, coaching programmes and establishing networks and communities of practice to sustain learning. She maintains her social work registration and her commitment to person centred and community focused approaches. Jane has a deep interest in the potential offered by new ways of working, designing and building organisations and communities that can best deliver this kind of service. She works with organisations and leaders to develop approaches that design in autonomy, wholeness and purpose. Archives

October 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed